The Beating Heart of a Civilization: Exploring the Ancient Wewas of Sri Lanka

Stand on the edge of a great Sri Lankan reservoir at dawn. The water, a vast, placid mirror, reflects the soft pastels of the sky. It feels ancient, natural, like it has always been there. But it hasn’t. That’s the first thing you need to understand about the incredible Ancient Wewas of Sri Lanka. These aren’t just reservoirs; they are the colossal, earth-and-stone arteries of a civilization that mastered water management over two thousand years ago. They are a testament to a time when kings thought in terms of raindrops and dynasties, and when engineers, armed with little more than string-levels and profound wisdom, sculpted the landscape to sustain a nation. This isn’t just about irrigation. It’s about a philosophy, a way of life that saw water as a sacred trust, a gift to be managed with incredible precision and foresight.

Key Takeaways:

- The ‘wewas’ of Sri Lanka are not just reservoirs but complex, man-made hydraulic systems dating back over 2,500 years.

- This ancient technology was central to the success of the Dry Zone kingdoms of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, enabling vast rice cultivation.

- Key engineering innovations like the Bisokotuwa (valve pit) allowed for precise control of water pressure, a concept not seen in the West for another 1,000 years.

- The wewas were interconnected through a sophisticated ‘cascade system’ that maximized water use, minimized waste, and supported entire ecosystems.

- More than just an agricultural tool, the wewa was the social, cultural, and ecological heart of the traditional Sri Lankan village.

What Exactly is a ‘Wewa’? It’s So Much More Than a Tank

Calling a wewa a ‘tank’ or ‘reservoir’ is technically correct but feels like calling a cathedral just ‘a building’. It misses the point entirely. The English words imply a simple container. A wewa is a living, breathing system. It’s an ecosystem. It was designed not just to hold water but to manage it, purify it, and distribute it with an efficiency that is, frankly, astounding.

At its core, a wewa is an artificial lake created by building a massive earthen embankment, or ‘bamma’, to trap monsoon rainwater. But it’s the components within this system that reveal the true genius behind them. You have intake canals (‘ul-ela’), outlet canals (‘yawa-ela’), spillways (‘wana’) to release excess water safely, and, most importantly, sophisticated sluice gates (‘sorowwa’) to control the outflow. The entire structure was meticulously planned, often using the natural contours of the land to its advantage. The scale is what truly boggles the mind. Some embankments stretch for miles and stand over 50 feet high, all built by hand, moving millions of tons of earth. Think about that for a second. No diesel engines, no excavators. Just human ingenuity and a profound understanding of hydrodynamics.

The Genesis of a Hydraulic Civilization

Sri Lanka’s north-central plains, the heartland of its ancient kingdoms known as the Raja Rata (‘King’s Country’), is a paradox. It’s called the Dry Zone. The region receives plenty of rain, but it’s concentrated in a single, intense monsoon season, followed by months of brutal drought. To build a thriving agricultural society here, especially one based on a water-hungry crop like rice, seemed impossible. The solution? Don’t just survive the monsoon; capture it. Every last drop.

The first small village wewas started appearing as early as 500 BCE. These were simple, local efforts. But as kingdoms grew, so did the ambition of their rulers. Visionary kings like Vasabha, Mahasena, and Dhatusena transformed wewa-building into a state-level enterprise. They weren’t just building for the next harvest; they were building for the next century. The culmination of this hydraulic obsession came during the reign of King Parakramabahu the Great (1153-1186 CE), whose famous decree echoes through history: “Let not even a small quantity of water that comes from the rain go to the sea without benefiting man.” He didn’t just repair existing wewas; he created a truly colossal interconnected system, the grandest of which is the Parakrama Samudra, or the ‘Sea of Parakrama’. It’s so vast that standing on its shore, you can easily mistake it for a natural ocean.

Engineering Genius: How on Earth Did They Do It?

Modern engineers with laser-guided equipment are still in awe of what ancient Sri Lankans accomplished. The gradients of the canals, the placement of the embankments, the understanding of water pressure—it’s all remarkably precise. Let’s look at a few of the key innovations that made it all possible.

The Bisokotuwa: A World-First Innovation

This is the real showstopper. The biggest challenge in releasing water from a massive reservoir isn’t opening a gate; it’s surviving the immense pressure. The force of the water can easily destroy a simple sluice gate. The ancient engineers solved this with the Bisokotuwa, or ‘valve pit’. It’s essentially a rectangular well built into the embankment, a short distance from the inner face. Water from the wewa enters the Bisokotuwa through an inlet conduit at the bottom. Inside this well, the water rises, and its turbulent energy dissipates. From there, it flows out calmly through another conduit under the embankment to the paddy fields. By regulating the flow within this pit using wooden gates, they could control the outflow with incredible precision and, most importantly, without compromising the structural integrity of the entire dam. It’s a sophisticated pressure-reducing valve, and it predates similar Roman engineering by centuries. It was the technological leap that allowed for the construction of truly gigantic reservoirs.

The Ellanga Gammana: The Brilliant Cascade System

Individual wewas are impressive, but the true genius lies in how they were connected. The Ellanga Gammana, or cascade system, is a network of small to medium-sized wewas built in a series along the natural drainage lines of a small valley. It’s a masterpiece of sustainable water management. Here’s how it works:

- The topmost wewa collects rainwater first. Its outflow, along with any seepage, doesn’t go to waste.

- It flows downstream to feed the next wewa in the chain.

- This process continues, wewa after wewa. Each reservoir in the cascade feeds the next.

- The system incorporates paddy fields, forests, and groundwater recharge pits. The trees planted on the embankments prevented erosion. The shallow areas of the wewa acted as natural silt traps and biodiversity hotspots.

This wasn’t just about irrigation. It was a holistic land management system that purified water, controlled floods, recharged groundwater, prevented soil erosion, and sustained a rich ecosystem. Every element had a purpose. Nothing was wasted.

The Yoda Ela: Canals of Unbelievable Precision

To move water from the massive storage wewas to smaller, distant tanks and fields, they built canals, or ‘elas’. The most famous is the Yoda Ela (Giant Canal). This 54-mile-long canal carries water from the Kala Wewa to the Thissa Wewa in the capital city of Anuradhapura. The mind-blowing part? Its gradient is estimated to be just **six inches to a foot per mile**. Six inches! Achieving that level of precision over such a vast distance without modern surveying equipment is almost beyond comprehension. It speaks to a level of topographical understanding and patient, meticulous work that is simply humbling.

The Giants: Exploring Famous Ancient Wewas of Sri Lanka

While thousands of wewas dot the landscape, some are true giants, legendary for their scale and the stories behind them. They are not just ruins; many are still fully functional and vital to Sri Lankan agriculture today.

Parakrama Samudra

Located in Polonnaruwa, this is the magnum opus of King Parakramabahu I. It’s a composite of five separate reservoirs linked together, with a surface area of over 5,300 acres and an embankment stretching for over 8.5 miles. It was the heart of his kingdom, supporting a population and an agricultural output that was the envy of the region. Today, it remains a breathtaking sight, a man-made sea that irrigates over 18,000 acres of paddy.

Kala Wewa

Built by King Dhatusena in the 5th century CE, the Kala Wewa has a story steeped in legend. The king’s own nephew, seeking the throne, demanded to know where the king’s ‘treasure’ was. King Dhatusena took him to the magnificent Kala Wewa, and gesturing to the life-giving water, declared, “This, my friend, is the whole of my wealth.” The story, though ending tragically for the king, perfectly captures the Sri Lankan reverence for water. The wewa’s embankment is over 3 miles long and 40 feet high, and it feeds the legendary Yoda Ela.

Minneriya Wewa

Built by the great King Mahasena in the 3rd century CE, this wewa is now the centerpiece of the Minneriya National Park. During the dry season, as the water level recedes, it exposes fresh grass and shoots. This attracts hundreds of elephants from all over the region in a phenomenon known as ‘The Gathering’—the largest meeting of Asian elephants in the world. It’s a powerful, living example of how these ancient structures don’t just support human life, but have become keystones of the natural world.

Beyond Irrigation: The Socio-Cultural Heartbeat

The wewa was never just about water for the fields. It was the gravitational center of the village. It was where life happened.

“The wewa was the source of life, the moderator of the climate, and the foundation of a collective, cooperative culture. Every aspect of village society, from governance to religious festivals, was tied to the wewa and the rhythm of its waters.”

The management of the wewa was a communal responsibility, fostering a strong sense of cooperation. Rituals were performed to honor the gods associated with water. The wewa provided fish for food. The surrounding lands offered medicinal herbs and grazing for cattle. It was a place for bathing, for socializing, for life to unfold. The health of the wewa was the health of the community. When a wewa was breached or fell into disrepair, it wasn’t just an infrastructure problem; it was a cultural catastrophe.

This deep connection is embedded in the language and folklore of Sri Lanka. There’s a rich vocabulary describing every part of the wewa and its ecosystem. The knowledge of how to maintain these systems was passed down through generations, a sacred duty held by the ‘Gamarala’ (village leader) and the elders. It represented a worldview where humanity and nature were not in conflict, but in a carefully balanced partnership.

The Wewas Today: A Living, Breathing Heritage

After the fall of the Raja Rata kingdoms, many of these great systems were swallowed by the jungle and forgotten for centuries. It was only during the British colonial period that many were rediscovered, their scale and sophistication shocking the colonial engineers. In recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for this ancient wisdom. Many wewas have been restored and are once again the backbone of agriculture in the Dry Zone. They are a powerful symbol of national pride and a potent reminder of a glorious past.

But they are also more than that. In an era of climate change, where water scarcity is a global crisis, the principles of the ancient wewa system have never been more relevant. The ideas of rainwater harvesting, integrated land management, maximizing every drop, and maintaining ecological balance are precisely the lessons the modern world needs to learn. The ancient engineers of Sri Lanka weren’t just building for their time; they were building for all time. They left behind a blueprint for sustainability, written in earth and stone across the face of their island nation.

Conclusion

To visit a wewa is to feel the pulse of Sri Lankan history. It’s to stand in the presence of a quiet, enduring genius. These vast, shimmering bodies of water are not silent relics of a bygone era. They are active, vital parts of the modern landscape, their waters still nourishing the fields and communities that depend on them. The ancient wewas of Sri Lanka are more than just an engineering marvel; they are a profound statement about the relationship between humans, water, and the earth. They teach us that with vision, cooperation, and a deep respect for nature’s cycles, it is possible to create a truly sustainable civilization that can thrive for millennia.

Find Your Zen: The World’s Most Calming Hotel Lobbies

Find Your Zen: The World’s Most Calming Hotel Lobbies  Find the Best Train Carriages for Quiet & Scenic Views

Find the Best Train Carriages for Quiet & Scenic Views  Hammock Reading: Finding Joy in Simple Pleasures

Hammock Reading: Finding Joy in Simple Pleasures  Create a Sensory Souvenir: Remember Your Trip Forever

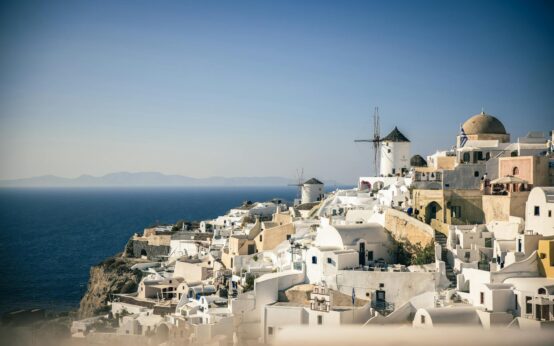

Create a Sensory Souvenir: Remember Your Trip Forever  The Calming Colors of a Santorini Sunset Explained

The Calming Colors of a Santorini Sunset Explained  Discover the World’s Best Planetariums: A Guide

Discover the World’s Best Planetariums: A Guide  Backtest Crypto Trading Strategies: A Complete Guide

Backtest Crypto Trading Strategies: A Complete Guide  NFT Standards: A Cross-Chain Guide for Creators & Collectors

NFT Standards: A Cross-Chain Guide for Creators & Collectors  Decentralized Storage: IPFS & Arweave Explained Simply

Decentralized Storage: IPFS & Arweave Explained Simply  How to Calculate Cryptocurrency Taxes: A Simple Guide

How to Calculate Cryptocurrency Taxes: A Simple Guide  Your Guide to Music NFTs & Top Platforms for 2024

Your Guide to Music NFTs & Top Platforms for 2024  TradingView for Crypto: The Ultimate Trader’s Guide

TradingView for Crypto: The Ultimate Trader’s Guide