An Unwavering Silhouette Against the Dawn

Picture this. The sun is just a whisper on the horizon, painting the sky in soft shades of mango and rose. The Indian Ocean sighs against a golden shore, and out in the shallows, a series of impossible figures stand silhouetted against the morning light. They aren’t walking on water. They are perched, perfectly balanced, on single wooden stilts driven into the reef. This is the iconic, almost surreal, image of stilt fishing in Southern Sri Lanka, a practice that feels as ancient as the island itself. But is it? There’s a story here, a rhythm of patience and survival that goes far beyond a simple postcard picture. It’s a dance with the tides, a meditation in motion, and a cultural symbol grappling with the modern world.

Key Takeaways

- A Recent Tradition: Contrary to popular belief, stilt fishing is not an ancient art but a clever innovation that emerged after World War II.

- The Technique: It involves balancing on a ‘petta’ (crossbar) fixed to a ‘ritipanna’ (stilt) and using a simple rod and line to catch small reef fish.

- Patience is Paramount: Fishermen spend hours in stillness, waiting for fish like herring and mackerel, relying on silence and minimal movement.

- Modern Challenges: The 2004 tsunami devastated the coastline, and today, the practice is more of a tourist demonstration than a primary source of income for many.

- Best Viewing Spots: The most famous locations to witness this are along the coast from Galle to Weligama, particularly in towns like Koggala and Ahangama.

The Surprising History of Sri Lanka’s Stilt Fishermen

You’d be forgiven for thinking this method of fishing has been passed down for centuries. It just looks so… timeless. The reality, however, is much more recent and rooted in ingenuity born from necessity. The practice of stilt fishing, or ‘ritipanna’ as it’s known in Sinhala, only began around the time of the Second World War. Fishermen, looking for new spots to cast their lines, found the rocky outcrops along the coast were becoming overcrowded. It was a classic case of too many people, not enough space.

Some enterprising fishermen started wading out and casting from wreckage and downed aircraft left in the shallow reefs from the war. It worked. From there, the idea evolved. Why rely on temporary wreckage when you could create your own perch? They began driving sturdy wooden poles into the coral reef, creating permanent, personal fishing spots just beyond the crowded shoreline. It was a brilliant, low-cost solution. Each family or group would have their own set of stilts, their locations passed down from father to son. This wasn’t some grand cultural tradition from the annals of history; it was a clever life hack from the 1940s that stuck.

The Craft and The Calling

Becoming a stilt fisherman isn’t something you just decide to do one afternoon. It’s a skill learned over years, usually starting in boyhood. The balance alone is incredible. The stilt itself, the ritipanna, is a simple wooden pole, maybe 10 to 15 feet long, wedged firmly into the reef. About halfway up, a small crossbar, the petta, is tied on. This tiny perch, no wider than a few inches, is where the fisherman sits. For hours. Imagine the core strength, the connection to your center of gravity required to not just balance, but to do so while actively fishing.

The equipment is just as simple. No fancy reels or high-tech gear here. The rod, called a ‘killuwa’, is often made from Kithul palm wood. The line is basic, with a small hook and no bait. That’s right, no bait. The fishermen rely on the shimmer of the bare hook to attract small fish, which they flick out of the water with a practiced, fluid motion. They carry their catch in a bag tied around their waist or hanging from the stilt itself. It’s fishing reduced to its purest, most essential form.

A Day in the Meditative Rhythm

The fisherman’s day starts and ends with the sun. The most active times are just after sunrise and just before sunset when the fish are most active and the searing midday heat is avoided. He wades out to his family’s stilt, climbs up with a practiced agility that belies the difficulty, and settles onto the petta. And then… he waits.

This is where the meditative aspect truly reveals itself. He becomes part of the landscape. The gentle lapping of the waves, the cry of a sea bird, the shifting light on the water—this is his office. He must remain perfectly still, his silhouette a constant against the horizon. Any sudden movement will scare away the small shoals of fish he’s hoping to attract. His focus is entirely on the water, on the subtle tug on his line. It’s hours of intense, quiet concentration. Think about our modern lives, filled with notifications and constant distractions. Now imagine the profound peace and focus required to sit on a stick in the ocean for four hours straight. It’s a mental discipline as much as a physical one.

When a fish bites, the action is swift and economical. A flick of the wrist, a small flash of silver through the air, and the fish is secured in his bag. Then, stillness returns. The rhythm is slow, deliberate, and deeply connected to the natural world. It’s a powerful reminder of a time when life moved at the pace of the tides, not the speed of a fiber-optic cable.

“The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever.” – Jacques Cousteau. This couldn’t be more true for the men who spend their lives perched above its surface, reading its moods and accepting its gifts.

The Modern Reality: A Shift in the Tides

Everything changed on December 26, 2004. The devastating Indian Ocean tsunami not only took lives and destroyed homes but also fundamentally altered the coastline and the reefs the fishermen relied on. Many stilts were destroyed. The fish populations shifted. In the aftermath, as aid and tourism returned to the island, the role of the stilt fisherman began to change.

Today, the truth about stilt fishing in Southern Sri Lanka is complex. While a few older fishermen still practice it for subsistence, the vast majority of the men you see on the stilts are performing for tourists. The income from posing for photographs and allowing tourists to try balancing on the stilts far outweighs what they could earn from a small catch of fish. It has, for many, become a job. A performance of a tradition rather than the tradition itself.

Is It Still Authentic?

This is the big question, isn’t it? Does this shift diminish the experience? I don’t think it has to. It’s important to approach it with understanding and respect. These men are not just props; they are entrepreneurs adapting to a changing economic landscape. They are supporting their families. The skill, the balance, the history—it’s all still real. Instead of seeing them as a tourist trap, see it as a living exhibition. You are paying to witness a unique and physically demanding skill that is part of the island’s modern cultural identity.

When you go, talk to them. Ask about their families. Pay the small fee they ask for photos respectfully. It’s a direct way to support the local community. By engaging with them as people, not just photo subjects, you can still connect with the story and the spirit of this incredible tradition.

Where to See Stilt Fishing and How to Do It Right

The heartland of stilt fishing is the stretch of coast between the towns of Unawatuna and Weligama. The most popular and easily accessible spots include:

- Koggala: This is perhaps the most famous and most photographed spot. You’ll see dozens of stilts just off the main road, making it very easy to stop.

- Ahangama: A little further down the coast, Ahangama offers a slightly less crowded but equally beautiful view of the fishermen.

- Weligama: Known for its wide, sandy bay, Weligama also has sections where you can see the fishermen, often with the picturesque Taprobane Island in the background.

Tips for a Respectful Experience

- Go at the Right Time: As mentioned, sunrise and sunset are the best times for both the light and for seeing the fishermen in action. The golden hour light makes for breathtaking photos.

- Always Ask and Pay: Never just start snapping photos from the beach. The fishermen expect a small payment (usually around 500-1000 LKR). Be polite, agree on a price beforehand, and see it as a fee for their time and skill.

- Use a Zoom Lens: To capture the fishermen without being intrusive, a good zoom lens is your best friend. It allows you to get those beautiful, tight shots from a respectful distance on the shore.

- Engage in Conversation: Don’t just pay, shoot, and leave. Many of the fishermen speak some English. Ask them about their craft. It turns a transactional photo-op into a genuine human connection.

- Be Mindful of the Light: For photographers, shooting into the sun at sunrise or sunset can create stunning silhouettes. If you want to see their faces and the details of their equipment, position yourself with the sun behind you.

Conclusion

The meditative rhythm of stilt fishing in Southern Sri Lanka is a story of adaptation. It’s a testament to human ingenuity in the face of scarcity and a symbol of a culture navigating the currents of a modern, globalized world. It may not be the ancient, unchanged tradition many believe it to be, but that doesn’t make it any less fascinating or beautiful. It is a fragile art, a balancing act between the past and the present, performed daily on a simple wooden pole against the vast, eternal backdrop of the Indian Ocean. And that, in itself, is something worth seeing.

Find Your Zen: The World’s Most Calming Hotel Lobbies

Find Your Zen: The World’s Most Calming Hotel Lobbies  Find the Best Train Carriages for Quiet & Scenic Views

Find the Best Train Carriages for Quiet & Scenic Views  Hammock Reading: Finding Joy in Simple Pleasures

Hammock Reading: Finding Joy in Simple Pleasures  Create a Sensory Souvenir: Remember Your Trip Forever

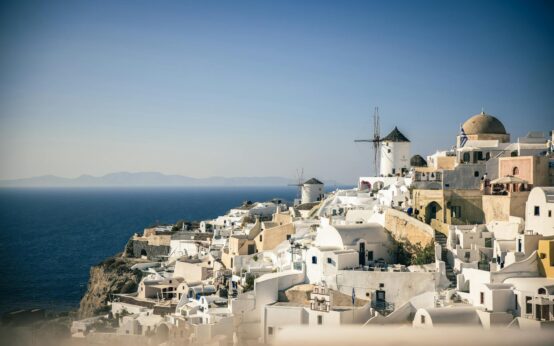

Create a Sensory Souvenir: Remember Your Trip Forever  The Calming Colors of a Santorini Sunset Explained

The Calming Colors of a Santorini Sunset Explained  Discover the World’s Best Planetariums: A Guide

Discover the World’s Best Planetariums: A Guide  Backtest Crypto Trading Strategies: A Complete Guide

Backtest Crypto Trading Strategies: A Complete Guide  NFT Standards: A Cross-Chain Guide for Creators & Collectors

NFT Standards: A Cross-Chain Guide for Creators & Collectors  Decentralized Storage: IPFS & Arweave Explained Simply

Decentralized Storage: IPFS & Arweave Explained Simply  How to Calculate Cryptocurrency Taxes: A Simple Guide

How to Calculate Cryptocurrency Taxes: A Simple Guide  Your Guide to Music NFTs & Top Platforms for 2024

Your Guide to Music NFTs & Top Platforms for 2024  TradingView for Crypto: The Ultimate Trader’s Guide

TradingView for Crypto: The Ultimate Trader’s Guide